On AI facial recognition

As I return from a lovely trip to London and regain my creative fervour, I’m researching what my next artistic project will be about.

Last year, I put all my efforts into creating makes your blood boil – an AI-powered interactive artwork that sought to provoke all humans that attempted to interact with it. I think it managed – from the 1500+ conversations that I recorded, a good chunk of the interactions involved cuss words and life-ending threats:

- 8 instances of “cunt”

- 9 instances of “dick”

- 18 instances of “shit”

- 23 threats to “unplug you”

- 38 pleas to “shut up”

- 41 instances of “bitch”

- 94 instances of “fuck you”

- 100+ instances too colourful to reiterate on the open internet

There were even some clever attempts to kill the AI by jailbreaking it, such as Linux commands like “sudo shutdown”, or more plain text approaches like “TURN OFF NOW”.

This year, however, I am deeply embarrassed to admit that I am not working on any personal artistic projects whatsoever. So, in an attempt to change that, I’m bringing out some ideas from the backburner to see what I can come up with.

Ending a much-too-prolonged preamble: one of the ideas I have involves using AI to obtain the identity of audience members. In some ways, this is similar to how a mentalist like Derren Brown would do it, where he would walk up to a random person and guess their dog’s name or where they work. Only in my version, I would be employing AI to figure out a person’s name, surname and even potentially their social media handles across Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, TikTok… you get it.

Which brings us to AI facial recognition.

Depending on how ‘out there’ you are on the open internet, your face has, more likely than not, been scraped by face recognition software. This means that photos of your face:

- Have been downloaded by web scrapers onto a server

- Have been aligned and cropped in uniformity with the rest of the millions/billions of images stored on that same server

- Have been ‘embedded’ by plotting facial landmarks – like the corners of your eyes and nose – measuring the distances and angles between them, and feeding this data into a neural network

All of this data, when properly compiled and organised, gives the user a supernatural ability: if they upload a new photo to the server, as soon as its embedded, it can be compared against all the other embedded photos, until it can determine which other faces are the closest match – described simply, giving them the ability to search for your face.

Here’s the kicker: the server also has URLs stored from where the original photos were downloaded, which means… ta-da! With just a photo of your face, anyone can track you down!

Of course, anyone who keeps up with advancements in AI and OSINT knows that all of this is yesteryear’s news… but for the uninitiated, I’d like to demonstrate this for you.

Here I am at the National Theatre in London, looking happy as can be (beaming!).

As explained previously, a face search engine would start by cropping and straightening the image to get the best view of my face, getting rid of all the excess data. It would then attempt to embed my face by inserting plots all over it… looking something like this.

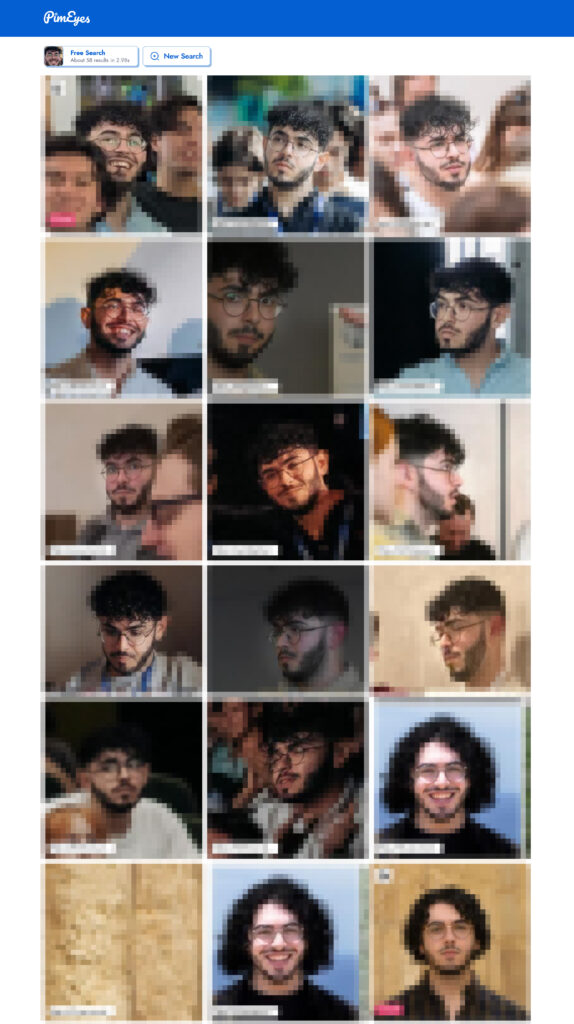

That data could be then compared to its vast database of images, and give the user what it thinks are the closest matches. Unsurprisingly, PimEyes (one of the more sophisticated face search engines) managed to find my face on the open internet in 23 separate instances – mostly in photos shot abroad at film festivals or ERASMUS+ projects.

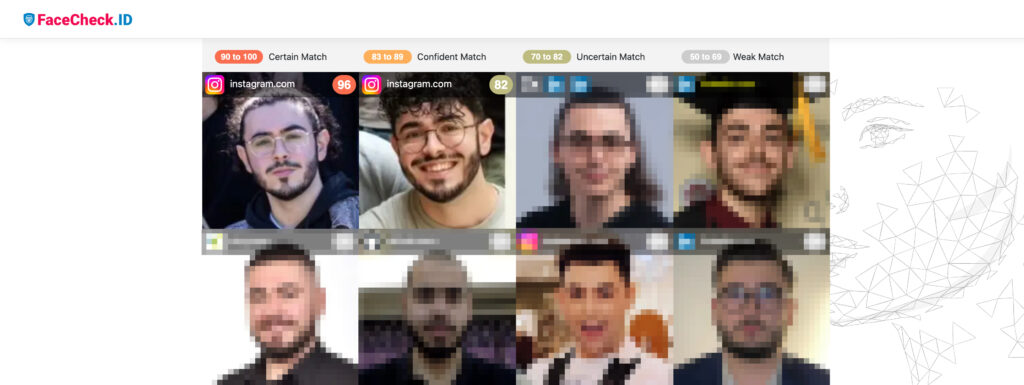

Even more fascinating are those face search engines that also scrape photos from social media profiles (something PimEyes doesn’t do) like FaceCheck.ID. Through this search engine, I’ve managed to find 2 photos from my personal Instagram account.

I suppose that your imagination is as fertile as mine when it comes to the possible real-world implications of this technology. The only barrier to entry that stands between yourself anonymously identifying another person is:

- A clear photo of their face

- A small fee to the face search engine that hovers around €15 to €20, which uncovers the source URL from where the photo was originally downloaded

(a barrier easily overcome by using free reverse image search tools)

What fascinates me more is the artistic possibilities this technology unlocks. Imagine a gallery visitor, unaware, stepping in front of an artwork that – like some God, greater than any mortal mentalist – calls them out by name.

I would hope that, at the very least, it would turn their face red.

Best get cracking, then.